After nearly half a century in custody for a murder he says he didn't commit, Leonard Peltier still hopes for freedom. Part 1

Part 1: Native American activist turns 79 in Florida prison

Leonard Peltier waits, hopes — and dreams of freedom.

The American Indian activist and longtime prison inmate said he has been battling injustice since he was 9 years old, so he understands the nelteed for patience.

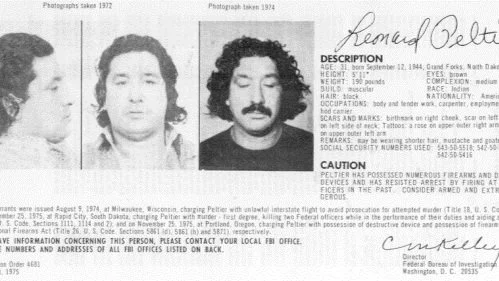

Now, after nearly half a century in prison after being convicted of shooting and killing two FBI agents in South Dakota, Peltier (seen above in a 1975 FBI wanted poster), who turned 79 years old on Sept. 12, is waiting to be told he can go home. He is hoping to be released, either by President Joe Biden or a federal parole board. Peltier said his fading health is another reason he should be allowed to go free.

But he will not admit to murdering FBI Agents Jack R. Coler and Ronald A. Williams on June 26, 1975, even if it would help him gain his freedom.

“No, I’m not the shooter,” Peltier told me during an exclusive phone interview from the Florida federal prison where he is being held. “I’m not the killer. I did not kill those FBI agents.”

That date, amazingly enough, is almost exactly 99 years after perhaps the greatest victory by Native American forces against the American military, the Battle of the Little Bighorn — known as the Battle of Greasy Grass by many Native Americans — which occurred in eastern Montana on June 25-26, 1876.

Almost a century later, on Feb. 27, 1973, about 200 American Indian Movement members seized control of the tiny village of Wounded Knee, the site of a Dec. 29, 1890, massacre of more than 300 Lakota men, women and children by the Seventh Cavalry. It was a flashpoint in the long history of tension and at times outright violence between Native Americans and whites in South Dakota.

During the 71-day standoff in 1973, Frank Clearwater, who was of Cherokee and Apache heritage, was shot and wounded on April 17 and died on April 25. Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont, who was a Lakota, was shot and killed on April 26.

Peltier was not at Wounded Knee during the 1973 standoff. But he was an activist on behalf of his people, and that led to his alleged involvement in a double murder in 1975.

Peltier was born on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa near Belcourt, N.D. As a teen, he attended Flandreau Indian School in eastern South Dakota before returning to North Dakota.

As a young man, he moved to Seattle, where he worked as a welder, a construction worker, and as the co-owner of an auto shop that also provided a halfway house for Native Americans freshly released from prison, as well as those battling an addiction to alcohol. His interest in Native rights was growing at the time.

Peltier joined AIM in 1972 at the invitation of founding member Dennis Banks. He did not take part in the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation, since he was in a Milwaukee jail, charged with the attempted murder of a police officer during a protest. Peltier was found not guilty of that charge in February 1978.

In 1975, he made it to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, with a goal, he said, of reducing tensions and preventing violence.

Peltier admits he was at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation when Coler and Williams were killed. Yes, he said, he was armed. But he insists he was not among the many men who fired upon the agents, and was not the person who shot and killed them after they were both severely wounded.

“My responsibility was to protect the elders and get the children out of there,” he said. “We were aware of an invasion the FBI was doing on the Pine Ridge Reservation.”

He said the FBI had hired Native Americans who were former members of the military as mercenaries and they were attacking homes, firing weapons and killing people. It was a very dangerous and tense time on the reservation.

“We were expecting some kind of assault by them,” Peltier said.

It was an extremely tense time, with many armed people on both sides. On Thursday, June 26, 1975, Special Agents Williams, 27, and Coler, 28, were seeking to arrest Jimmy Eagle, who was wanted on suspicion of the recent abduction and assault of two young ranchers in nearby Manderson.

Williams and Coler, driving separately, pulled into the Jumping Bull Compound around noon and were headed toward a red and white Chevrolet Suburban van that they believed held the man they were after.

An explosion of gunshots soon filled the summer air. The two vehicles driven by the FBI agents were pockmarked with holes; an estimated 125 bullets struck the vehicles, and more missed the cars. Some struck Coler and Williams.

Coler was shot in the right arm, which was bleeding profusely and nearly severed. He lapsed into unconsciousness. Williams, hit in the left shoulder and right foot, removed his shirt and tried to fashion a tourniquet to stem Coler’s bleeding.

As they lay wounded, some men approached the agents, and witnesses reported hearing three shots. Williams raised a hand to shield himself or ask for mercy, but a bullet tore through it and struck him in the face, killing him.

Coler was shot twice in the head, killing him.

A Native American, Joseph Stuntz, 23, also was killed. Stuntz, a member of the Coeur d’alene Tribe, was named Joseph George when he was born on Lapwai Reservation in Idaho. He attended an Indian boarding school in Indiana, where he was later adopted by an older white couple named Stuntz, was drawn to western South Dakota both to learn more about Native heritage and to join and support Native Americans fighting for their rights and dignity. He was shot in the back and found dead in the aftermath of the gun battle.

Stuntz was reportedly wearing a green SWAT fatigue jacket with “F.B.I.” on the back that had apparently been taken from the trunk of Coler’s car. Stuntz was buried on the Pine Ridge Reservation. According to an online account of his life supposedly written by a childhood friend, a Native holy man named Leonard Crow Dog gave him the Lakota name Joe Killsright Stuntz.

Four men were indicted for two counts of first-degree murder and aiding and abetting for the murders of Williams and Coler. Charges were dropped against James Theodore Eagle, while Robert Eugene Robideau and Darrelle Dean Butler were acquitted in a U.S. District Court in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on July 16, 1976.

Peltier had fled the country. He was arrested in Canada and extradited back to the United States.

In 2004, Bob Newbrook, a former Hinton, Alberta, police officer, claimed he arrested Peltier and later turned him over to the FBI, which announced it had captured the fugitive. Newbrook has said he regrets making the arrest and believes Peltier was illegally extradited back to the United States.

However, many of Peltier’s supporters, including his longtime lawyer Bruce Ellison of Rapid City, said they doubt Newbrook’s story.

Peltier said he was wrongfully returned to the United States and that was the beginning of a series of illegal and unethical events.

“They railroaded me into prison,” he said. “They railroaded me from Canada. I ain’t lying. We can prove it.”

Peltier has maintained his innocence for decades. In an interview with the CBS News program “60 Minutes” first aired on May 24, 1992, he told correspondent Steve Kraft he did not kill Coler and Williams.

“No, I did not,” Peltier said. “No, I never kills those agents.”

However, he did tell Kraft for the story “The Last Sioux Brave,” which is available online, that he was at the campground and was armed.

“Yes, I fired at them,” he said.

Why, Kroft asked.

“Because they fired at me and I fired back,” Peltier said.

He said he saw “two individuals in a red pickup” drive down to where the FBI agents were pinned down and wounded. The passenger got out and … “that’s about as far as I can go,” Peltier said.

He said he knew their identities, but would not disclose it.

An interview with a man wearing a stocking cap, mask and sunglasses is part of the report. The man was interviewed by author Peter Matthiessen, who wrote “In The Spirit of Crazy Horse: The Story of Leonard Peltier and the FBI’s War on the American Indian Movement.”

The man, identified as “Mr. X,” said Peltier and others were firing on the agents, and he advanced upon them and found them wounded but still battling. One of the agents fired a pistol, he claimed, and he responded by shooting and killing both men.

“Mr. X” said even if he came forward, he believed Peltier would remain in prison. Peltier said he would not identify anyone involved.

“I’m not a rat, I’m not a snitch, I’m not an informant,” he said.

Peltier said that if he identified anyone involved in the shooting “in my heart, in my mind, would be treason.”

He said the FBI agents were “the enemy” and were part of an organized effort to oppress and “nearly exterminate my people.” Peltier said he is not a murderer, and said he was standing up for Native American rights.

“The only thing I’m guilty of is trying to help my people,” he said. “That’s the only thing I’m guilty of.”

Peltier’s extradition was connected to affidavits given by Myrtle Poor Bear of Allen, S.D.

Poor Bear made three statements to FBI Special Agents Bill Wood and David Price.

In her first affidavit, she said she did not witness the shootings but Peltier, whom she said was her boyfriend, gave her a vivid account of them.

In a second one, she claimed to be an eyewitness, and provided extensive detail. In a third statement, she added to her story. The second and third affidavits were among the documents used to extradite Peltier back into the United States and take him to trial.

Poor Bear, however, was deemed incompetent to testify at the trial.

In 2000, Poor Bear recanted her story during a hearing in Toronto, Canada. She said she had never even met Peltier, much less lived with him and been his girlfriend.

According to the Native American issues and information site dickshovel.com, Poor Bear said FBI agents pressured and threatened her for months to force her to invent a story that would allow them to extradite Peltier from Canada. They showed her photos of the murder scene and finally took her there to help firm up her story.

The agents also said AIM members would kill her, Poor Bear said.

“They told me they were going to take my child away from me,” she said. “They told me they were going to get me for conspiracy, and I would face 15 years in prison if I didn’t cooperate. They said they had witnesses who placed me at the scene.”

Peltier said that alone should be enough to free him from prison.

“I’m hoping we can reveal, we can expose this,” he said. “These are serious constitutional violations. I’m hoping people understand I did not get a fair trial. If I had gotten a fair trial, I never would have spent a day in jail.”

Tom Lawrence has written for several newspapers and websites in South Dakota and other states and contributed to The New York Times, NPR, The Telegraph, The Daily Beast and other media outlets.