VP Vance: ICE agents have absolute immunity. USD law school prof: ‘No such a thing’ as absolute immunity for agents

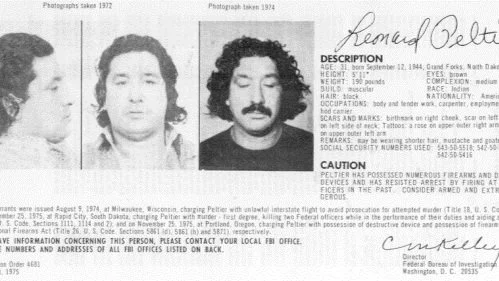

Vice President Vance asserted on January 8, “That guy is protected by absolute immunity.” The “that guy” is the ICE agent who shot and killed Renee Good on January 7 in Minneapolis. Legal experts have characterized the Vice President’s assertion as overstated. But it’s not totally wrong, either. There exists some immunity for federal law enforcement actions.There is also some immunity for state actors, but what is still mostly untested is whether state actors can face civil liability for cooperating with federal actors when widespread constitutional violations are taking place.

The State of Minnesota clearly has jurisdiction to charge the agent with a criminal offense in connection with Good’s death if the evidence warrants it. A reasonableness defense is available to state criminal charges against federal agents, but there is no such thing as absolute immunity such as that enjoyed by judges and legislators in the discharge of their duties. The agent could also be charged under a federal criminal law.

A civil cause of action – such as a wrongful death lawsuit against ICE by Good’s next of kin – is quite a bit more complicated. Some background is in order. A federal statute permits individuals to sue state actors for constitutional violations like excessive force by police officers. It is codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Section 1983 authorizes lawsuits against persons acting “under color of state law” – as well as non-state-actors acting in concert with them to commit constitutional deprivations. Attorneys’ fees are also recoverable if the plaintiff is successful.

Section 1983 does not apply to ICE agents because they are acting under color of federal law, not state law. And even state actors are entitled to “qualified immunity” – which means just what the term signifies, immunity, but qualified; not available in every case.

To sue an ICE officer, the Good family would likely frame a lawsuit against under the Federal Tort Claims Act (or FTCA). The long list of exceptions to liability articulated in this law were nicely outlined by Justice Gorsuch just last year in the case of Martin v. United States. That case involved a predawn FBI raid of the wrong house, a quiet family home. Neither the street name nor the address number matched the house the officers were supposed to enter. A SWAT team detonated a flash-bang grenade and assaulted the innocent occupants before realizing their mistake.

Although the FTCA waives the sovereign immunity of federal officers for torts they commit, it excepts a number of intentional torts (e.g., assault, battery, false arrest, malicious prosecution, etc.). The FTCA also contains a “discretionary-function exception” and a “law enforcement proviso” which countermands some – but not all – of the intentional tort exceptions. The Supreme Court held that the law enforcement proviso overrides the intentional-tort exception but not the discretionary-function exception. If you’re up for a mind-numbingly dense and technical analysis of statutory language, this is the case for you.

The upshot of the Martin decision is that we now know that (1) lawsuits against federal law enforcement officers for “assault, battery, false imprisonment, false arrest, abuse of process, or malicious prosecution” are allowed but (2) the government may escape liability if it can show its officers’ acts were discretionary. The plaintiffs had practically begged the court to articulate more clearly what the discretionary-function exception actually meant, but Justice Gorsuch declined, writing, “It is work enough for the day to answer the questions we took up this case to resolve.”

Some case law indicates that the discretionary-function would not protect federal officers from constitutional violations since “government officials never have discretion to violate the Constitution.” The discretionary-function exception relates to judgements and policy decisions like allocating more fire department resources to one neighborhood instead of another.

It appears that the plaintiffs in the Martin case might succeed. The law of discretionary-functions, however, is muddled and even judges have complained how difficult it is to apply.

The best answer to the question, “Does ICE have immunity for its actions?” is “It depends (on the application of the discretionary-function exception).”

Thomas E. Simmons is a professor at the University of South Dakota Knudson School of Law in Vermillion. His views are his own and not the views of USD, its administrators, or the South Dakota Board of Regents. The opinions expressed above are those of a humble private citizen.

Photo: public domain, wikimedia commons

The South Dakota Standard is offered freely and is supported by our readers. We have no political or commercial sponsorship. If you'd like to help us continue our mission to advance independent political and social commentary, you can do so by clicking on the "Donate" button that's on the sidebar to your right.

Follow us and comment on X and Bluesky